Update February 2022: All code examples from all articles in this series can now be found on Github in one repository

Welcome back, Adventurer. I apologize for the long wait between articles. I got caught up in other things. But now we’re back!

Last time, we created a simple sprite. In this article, we will take a closer look at the SNES architecture and memory mapped registers. And then finally display the sprite from last time.

Displaying a Sprite

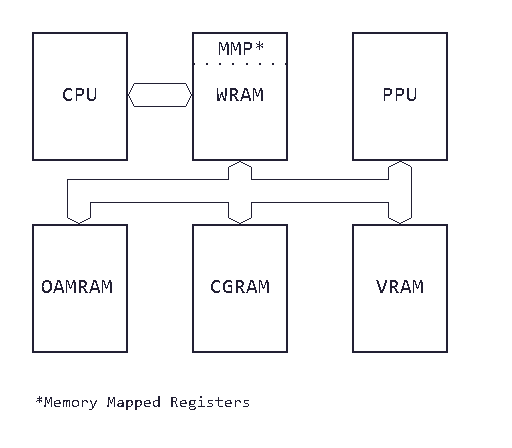

We will discuss the architecture of the SNES in the next articles in more detail. For now, look at this simplified overview:

Here is a summary of all components. The CPU or Central Processing Unit is the main processor of the SNES, this is the 65816 that will run the code we write. The PPU or Picture Processing Unit is responsible for rendering and sending data to the TV screen. The PPU has its own separate RAM that we cannot access directly.

As shown in the picture above, the SNES has four distinct sections of RAM:

- WRAM: Work RAM. This is the general RAM we can fully access and use for pretty much anything we want; graphics, variables, tables, etc.

- VRAM: Video RAM. Here is where we will store the graphics data we want to display. We will place the sprites we created last time here.

- CGRAM: Color Generator RAM. This is a special portion of RAM that will hold the actual color data.

- OAMRAM: Object Attribute Memory. Another special portion of RAM. Here we store the information to tell the PPU where to draw which sprite. We return to OAM in a moment.

(I left out the audio portion on purpose. I will cover audio in a later article.)

So, for the SNES to display our sprites we need to move the sprite data to VRAM, and the palette data to CGRAM. How do we do that? Memory Mapped Registers is the answer.

Memory Mapped Registers

When utilizing this technique, we reserve certain portions of the memory map (i.e., a range of memory addresses) for special purposes. In the case of the SNES, the addresses $xx:2100 through $xx:2143 are reserved to send commands and data to the PPU.

In the Links and References section at the end of this article, you’ll find a link to a list of all Memory Mapped Registers of the SNES. Use this list while you work through the code example below to understand the commands we send to the PPU.

This is also the only way for us to access VRAM, CGRAM, and OAMRAM. We tell the PPU that we want to change the data in one of these memory sections. Then send the (new) data we want to be changed/written to PPU RAM. Simple as that.

Object Attribute Memory

OAM or Object Attribute Memory is a section within PPU RAM reserved for a special purpose. Once we have the graphics and color data (from Sprites.vra and SpriteColors.pal) loaded into VRAM, we also need to tell the PPU where to draw which sprites on the screen.

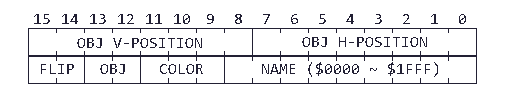

This is what OAM does for us. Every sprite we want to display needs four bytes of information in OAM:

These parameters control how a sprite is displayed/rendered by the PPU:

- H-Position: The horizontal position in pixels

- V-Position: The vertical position in pixels

- Name: Which sprite from the sprite sheet to display

- Color: A 3-bit number, select which out of eight color palettes to use

- Obj: Set the priority relative to backgrounds

- Flip: Whether to flip the sprite horizontally and/or vertically

We’ll discuss Obj and Flip in more detail in a later article. For now, we won’t use them/set them to zero.

That should be enough to understand the demo of this article. Let’s see all this in action and make some sense of it.

The Source Code

Okay, finally we get down to business. Here is what the code example will do:

- Load

Sprites.vrainto VRAM - Load

SpriteColors.palinto CGRAM - Load OAM data into OAMRAM

- Get stuck in an endless loop

Please keep two things in mind. First, I’ll introduce you to a few new opcodes. We’ll not discuss them in full detail yet, because most of them are just variants of opcodes you already know (can you guess what LDX does?). But I will discuss them in more detail in the next articles. Second, this is definitely not the way you want to do this. There are more effective ways to move data to (and from) PPU RAM. This example’s focus is to understand how memory mapped registers work.

Let’s look at the code:

Wow, that’s a lot of code! Let’s dissect this line by line:

Lines 1 through 18: In the first article we talked about labels and how they make the code more readable. These are a few labels we use to address the memory mapped registers I talked about earlier. We will discuss each register’s function in more detail as we move along.

Line 21: This is a simple assembler instruction for the ca65 assembler. It tells it that we are writing 65816 code (because ca65 can also compile 65C02 code).

Lines 25 through 27: This is where we load Sprites.vra and SpriteColors.pal into our ROM. We designate labels to the places where we load them into our ROM file. We will use these labels to access the data loaded here.

Lines 34 through 40: The ResetHandler is the entry point of our demo (we will see shortly why execution starts here). The first six lines of code are pretty standard and you will probably use them in all of your future SNES games. They include two new instructions, SEI and XCE:

sei : SEt Interrupt disable

xce : eXchange Carry and Emulation flagsSEI will disable interrupts. Think of interrupts as external signals that interrupt the current execution of the CPU and instead it executes a special subroutine called an interrupt handler. The NMIHandler subroutine is such an interrupt handler we will discuss it shortly.

Next, we switch the 65816 to native mode. These are the two instructions I teased last time when we talked about native and emulation mode. First, let’s look at XCE. This opcode will exchange the carry and emulation flag within the processor status register. Remember, that the 65816 starts in emulation mode and we need to switch it to native mode first to use all of its 16-bit features. This is exactly what lines 36 and 37 do: First, we clear the carry flag, then we copy (i.e., exchange) the carry into the emulation flag. Once the emulation flag is cleared, the 65816 will run in native mode. I told you it isn’t that hard.

The next three instructions use memory mapped registers to send commands to the PPU. The general workflow here is that we first load a certain bit mask (i.e., command) into the accumulator and then send that command by writing it to the appropriate (memory mapped) register. First, we use INIDISP to tell the PPU to force v-blanking. V-blank is the period when the cathode ray of a CRT resets itself each frame to the upper-left screen position. So it is ready to draw the next frame on the screen. When we force v-blanking, we tell the PPU not to draw anything to the screen as we are in “constant v-blank”. This is often done when we initialize the SNES on startup or when we load a new level, etc. Then we use NMITIMEN to tell the SNES to stop emitting NMI. NMI or Non-Maskable Interrupt is the most important interrupt. It occurs every v-blank or every time the SNES finishes drawing a frame. STZ is a new opcode, but it is just a convenient shortcut:

stz : STore ZeroWhich is the equivalent of

lda #$00

sta $ceff

; is the same as

stz $ceffLines 43 through 47: Now we want to transfer data from our ROM (which would be on a game cartridge) to the VRAM inside the SNES. As I told you earlier, we cannot access VRAM directly. Instead, we again rely on memory mapped registers to tell the PPU what we want to do.

First, we use VMADDL and VMADDH (VRAM Address) to tell the PPU where in VRAM we want to store our data. Since the SNES has 64KB of VRAM, we need a 16-bit or two-byte address to address VRAM completely. We set both address bytes to zero, so we will store our sprite data starting at $0000 in VRAM. We additionally tell the PPU to auto-increment the VRAM address once we have written a word (two bytes) to it. So every time we write data to VRAM, the PPU will automatically increment the VRAM address, so we don’t have to set the address for each data byte separately after every write (which is possible, but highly inefficient).

Next, we set the index register X to zero. We will use it as a loop counter and offset/index at the same time. This is a technique you will encounter and use a lot when writing SNES or 65816 code in general. So pay close attention to what happens in the loop:

Lines 48 through 56: First, we get the first byte of the sprite data. Here we use a new addressing mode called Absolute Indexed Addressing. This addressing mode will simply take the absolute address (two-byte address) and add the content from the index register X to calculate the effective address:

So, the accumulator now holds the first byte of the first sprite (loaded from the effective address SpriteData + X = SpriteData + $00). We use the (memory mapped) register VMDATAL to write the data to VRAM. Then we use INX to increment X by one (i.e., we add one to the current value in the index register X; X = X + 1). Now we use again Absolute Indexed Addressing to get the next byte (this time from the effective address SpriteData + X = SpriteData + $01). We use VMDATAH to write the second byte to VRAM. We increase X again. Now we check whether X is smaller than $80 (we want to transfer 4 sprites, each 32 bytes long, so we need to transfer a total of 4 * 32 = 128/$80 bytes). If X has not reached $80 yet (so there is more data to transfer to VRAM), we branch/jump back to the beginning of the loop with BCC. Review the simple game logic example from a previous article if you’re not sure how this works. Once 128/$80 bytes have been transferred, our four sprites are stored in VRAM starting at VRAM address $0000.

You might be wondering why we use two different (memory mapped) registers to write data to VRAM. It is because we are still using 8-bit registers. When we start using 16-bit registers in the next article, we will revisit this code example and improve it to use 16-bit registers, then the use of two (memory mapped) registers will make more sense (basically, the 65816 is a little-endian processor, when we store a 16-bit register to memory, the CPU will automatically store the low byte first, then write the high byte to the next memory location; again, the next article will explain this in detail).

Lines 59 through 70: This is pretty much the same as the loop for the sprite data above. Except for this time we use the (memory mapped) registers for CGRAM instead VRAM. We set the address we want to write in CGRAM to $80. Why $80? CGRAM has a total size of 512/$100 bytes. Since each color in BGR555 format takes two bytes (or one word) to store, we can store a total of 256 colors in CGRAM. In CGRAM we use the lower half ($00 ~ $7f) for background tiles, and the upper half ($80 ~ $ff) for sprites (sometimes called objects in SNES-related literature).

Line 72: This is a special instruction. $42 equals WDM, this instruction was reserved for future use but never implemented. So executing opcode $42/WDM will do exactly nothing. The bsnes+ emulator can use this opcode as a breakpoint for single stepping code.

Lines 74 through 112: Next, we load the OAM data into OAMRAM. We can handily derive all the numbers we need to store in OAMRAM. We take the screen resolution, divide it by two to get to the center of the screen and subtract the size of the sprite. Note that the sprite position is always pinned to the upper-left corner of the sprite.

By now, you surely know the drill. First, use the OAMADDL and OAMADDH registers (OAM Address) to tell the PPU where in OAMRAM we want to store our data. Then we use OAMDATA register to actually write data to OAMRAM. Remember that we don’t need to set the address after every write manually. The PPU will increment the OAMRAM address automatically after every write to OAMDATA.

Before we move on, a short reminder. The above example is highly ineffective. It is meant for educational and demonstration purposes only. In the next article, we will revisit this example and rewrite the code. There we will discuss and introduce subroutines (most often called functions in other programming languages).

Our code now so far transfers the sprite data to VRAM, color/palette data to CGRAM, and the OAM data to OAMRAM. So all data is in place. How do we tell the SNES to finally render anything? That’s what the next lines of code do.

Lines 114 through 122: First, we turn on objects/sprites by writing $10 to the Main Screen Designation. Why main screen? The SNES can display up to 128 sprites and four layers of backgrounds. Besides the main screen, we can render to mask windows and sub screens for special effects. For example, the keyhole screen transition in Super Mario World is done with sub screens. Certain transparency effects can be achieved this way. For now, remember that before we can display sprites or backgrounds, we need to tell the PPU that we want to render them on the main screen.

Next, we release forced blanking, which means that the PPU will actually execute render commands. In the same command, we also set the screen brightness to maximum.

Finally, we turn on NMI. This means the SNES will send an interrupt signal on every v-blank. Only during v-blank (or forced blanking) can we manipulate data in VRAM, CGRAM, or OAMRAM. If we try to write data to VRAM during v-blank, the PPU will simply ignore those commands. I’ll explain the NMI subroutine in a moment.

Now we jump to GameLoop. This is where most of the code you write will be executed. Starting at line 145 you can also see the NMIHandler subroutine. These two routines are the most important in your project. Here’s generally how your game will work:

- You start by initializing the most important (memory mapped) registers, load data into VRAM, OAMRAM, CGRAM, etc. (remember that we are completely ignoring anything to do with audio; there’s still some way to go until we get there)

- Then when you have released forced blanking, the PPU starts drawing to the screen. While the PPU is rendering your data from PPU RAM onto the screen, the code in your main game loop (here called

GameLoop) will execute. Here is where you want to do everything related to game logic; reacting to input, calculating a new sprite position, update the player’s score, etc. But you cannot send any commands to the PPU while it is rendering. - Once the PPU has finished rendering the screen, it will issue a non-maskable interrupt to signal that. An interrupt will finish the execution of the current opcode. After that, it calls the non-maskable interrupt subroutine, here named

NMIHandler. Now we’re in v-blanking. This means that the electron beam of the TV is moving from the lower-right corner back to its initial position in the upper-left corner. Only during a non-maskable interrupt can we send commands to the PPU and therefore update any graphics.

If this is confusing to you, I’ll put a link in the Links and References section at the end of this article. In the next article, we will get to 16-bit programming in more detail and introduce Direct Memory Access or DMA. Then this will make a lot more sense. Go read that article after you finished this one. Then return here and see if it makes more sense.

So in short: Do game logic in your main game loop, and do graphics in your NMI subroutine/handler.

Lines 132 through 139: This is our main game loop. There are only two instructions in it yet. The first, WAI simply stands for Wait for Interrupt:

wai : WAit for InterruptThis is a new 65816 instruction. When executing it, the CPU will stop executing until an interrupt occurs. There are other interrupts on the 65816, but we only need to concern ourselves with the non-maskable interrupt. All other interrupts are not used by the SNES.

Why would we want to wait on the NMI while we’re in the main game loop? Here’s a simple scenario:

Image your game is running. So, the PPU starts rendering to the screen. Let’s say the code in the main game loop read the joypad and then updates the OAM to reflect that the player’s sprite has been moved. Now the code in the main game loop is finished but the PPU is not yet done rendering the screen. If the main game loop would simply run again, the player’s sprite may be moved twice, while the updated OAM has never been rendered to the screen. This might cause the player’s sprite to glitch or jump around the screen.

Lines 145 through 151: This is the subroutine that is called every NMI (i.e., after the PPU has finished rendering the current frame to the screen). lda RDNMI is the first instruction that should be executed in every NMI handler. It basically tells the PPU that we acknowledge that the interrupt has occurred and that we will handle it. Finally, after we have done all the graphics stuff (in this example, none), we return to the main game loop. For this, we use a special opcode that can only be used in interrupt handlers:

rti : ReTurn from InterruptThe next article will concentrate on new programming techniques, 16-bit functionality, and subroutines. Once I have introduced you to subroutines, this opcode will make a lot more sense. For now, remember that after we have handled the interrupt, we tell the CPU to return to the main game loop with RTI.

Lines 166 through 177: The final section is the reset vector. When the 65816 starts up, it somehow has to know where to start execution. This is what the reset vector does. In the last 28 bytes of the first bank (i.e., $00:ffe4 ~ $00:ffff) we store the addresses of the reset handler and the interrupt handlers. I’m going to skip this for now, since this article is already getting too long. For now, remember that the address where the 65816 (and therefore the SNES) will start executing your code. Think of your reset handler as the main() function of your program. This is where execution will start when the program is loaded.

I’m going to skip ahead now and let you build your very first ROM that displays a sprite. Place SpriteColors.pal and Sprites.vra from the last article, SpriteDemo.s from above and this file in a new directory (e.g., /assemblyadventure/lesson04/):

Then open a command line, navigate to your new files, and execute these commands:

ca65 --cpu 65816 -s -o SpriteDemo.o SpriteDemo.s

ld65 -C MemoryMap.cfg -o FirstSprite.smc SpriteDemo.oThere should be a new file called FirstSprite.smc. Mind the upper-case C argument in the second command. Open it in bsnes+. Remember to choose compatibility mode when starting bsnes+ (else, it won’t work correctly; this is because we haven’t initialized the SNES yet. compatibility mode takes care of that for us. I’ll show you how to do this soon):

Congratulations, you just displayed your very first sprite on the SNES! To be precise, you displayed four sprites.

If you wonder why there is an extra sprite in the upper-left corner there is a simple explanation. The SNES can display up to 128 sprites simultaneously. Since we only use the first four sprites, and the other 124 sprites are set to zero, the SNES will display sprite zero 124 times at position (0, 0) (OAMRAM for sprites 4 ~ 127 is completely set to zero).

Conclusion

If this article feels a bit rushed, don’t worry. I wanted to describe the code example in its eternity. To keep this to a reasonable length, I had to skip some details. So in the next article, we will look at more advanced programming techniques and finally start to harness the 16-bit powers of the 65816. We will look at subroutines specifically. An important tool for reusing code in larger projects.

Links and References

- Here’s a complete list of all the Memory Mapped Registers of the SNES. Bookmark this link, I’ll reference it often in the future.

- In this repository, you will find a similar example like the one I showed you in this article.

- Here is another good introduction to how NMIs work.

- All SNES Assembly Adventure code examples of this series on Github