Update February 2022: All code examples from all articles in this series can now be found on Github in one repository

Welcome back, Adventurer. In this article, I’ll introduce you to subroutines. You will learn

- What the stack is and how it works

- What subroutines are and how they work

We’ll write a simple subroutine that adds the value in register X to the value in register Y.

But before we dive deeper into subroutines, we first need to introduce the stack. I’ll probably come back to the stack several times in future articles since it’s such a great and important concept to understand. So this is by no way a complete description of the stack and all its functionality.

The Stack

The stack formally called a LIFO (last-in, first-out) structure, is a certain range of memory locations where we can store data. The most important characteristic of a stack is that it is a chronological structure. So whatever data we pushed last onto the stack, is the first data that gets pulled from the stack.

When we want to place data on the stack, we say we’re pushing onto (the top) of the stack; when we want to retrieve that data again from the stack, we say we’re pulling data from (the top of) the stack (Note: Some processor architectures use pop instead of pull; popping and pulling from stack are the same thing, just different words).

Imagine a stack of plates: Whenever we push a plate on top of the stack, we first need to pull the last plate we put on top of the stack before we can pull any of the plates beneath it.

Here is how the stack on the 65816 works. I’ll first describe the operations in general, then I’ll show you some code examples.

Whenever we push data onto the stack, the 65816 takes the value inside the internal stack pointer or SP and decrements it by either one, two, or three (we will see shortly why). Then it uses the new stack pointer (+1) as the address to store the data in memory. I’ll explain the ‘(+1)’ in a moment.

Whenever we pull data from the stack, the 65816 loads the data from the address stored in the stack pointer (+1), then increments the stack pointer by either one, two, or three.

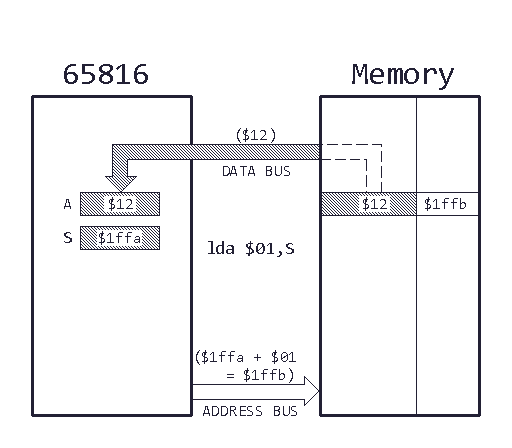

Here is what the ‘(+1)’ part in the paragraphs above means: The stack pointer on a 65816 always points one byte beyond the data we last pushed onto the stack. For example, if the stack pointer currently holds the value $1ffa and we pull one byte from the stack, the data stored at address $1ffb (stack pointer + 1) will be pulled, and the stack pointer set to $1ffb.

Likewise, if we push two bytes onto the stack, the stack pointer will decrement by two from $1ffa to $1ff8, the two bytes we push onto the stack are then stored at the addresses $1ff9 and $1ffa respectively.

Let’s make this a bit clearer with a simple code example. This code will also include code to switch the 65816 from emulation to native mode and set the index registers X and Y to 16-bit, while the accumulator will operate in 8-bit mode.

Lines 4 through 10: This shouldn’t be a surprise for you. We switch the 65816 to native mode, set the index registers to 16-bit, the accumulator to 8-bit, and set up the stack pointer to start at $1fff.

Lines 13 through 15: We load A, X, and Y with different values.

Lines 17 through 19: We push all three working registers to the stack.

Lines 21 through 23: Now we pull all three values back into the registers. Observe how we switched the order in which registers values are pulled from the stack. The last value we pushed onto the stack was from Y. After that, we pull that value back into X, and then we pull the next value from the stack into Y. So X and Y have switched values.

This is a very simple example. In the next section, we’ll see how the stack can help us write modular code. If you struggle to understand this code, try tracing the values of all registers after each opcode is executed.

Here are the new opcodes you just learned:

pha : PusH Accumulator

phx : PusH X register

phy : PusH Y register

pla : PulL Accumulator

plx : PulL X register

ply : PulL Y registerSubroutines

If you’re familiar with any programming language, you have most probably heard of functions (sometimes also called procedures). Functions are one of the most fundamental units of any programming language. It helps us to abstract our program and reuse code.

When programming in 65816 machine language, we call these programming units subroutines instead of functions. But they are (more or less) the same thing.

When we call a subroutine in our code the following will happen: The 65816 will push the program counter or PC onto the stack (this is the return address where execution will resume after the subroutine is done). Then it will jump to the subroutine and continue execution from there. Once the subroutine is done, we tell the CPU to return to where it left off before by pulling the return address we pushed onto the stack earlier back into the PC.

Let’s write a simple example. We want to write a subroutine called AddXtoY. This subroutine will execute a 16-bit addition: It will add the value in the register X to the value in register Y (and store it in Y).

As always, I’ll first show you the code, then discuss it in detail.

Let’s go through this line by line.

Lines 4 through 10: You know the drill. We switch the 65816 to emulation mode, set the index registers to 16-bit, the accumulator to 8-bit, and set up the stack pointer to start at $1fff.

Lines 13 and 14: Here we store the values we want to add. No surprises here either.

Line 15: Now, this is where the interesting stuff happens. First, here’s a new opcode:

jsr : Jump to SubRoutineIn this case, we use absolute addressing to call the subroutine. Here is how it works: First, the CPU pushed the current program counter + 2 onto the stack (so when we return from the subroutine, execution will resume at the instruction after jsr). Then, the operand is loaded into the program counter. In our example, the address of AddXtoY is loaded into the program counter and execution will, therefore, resume from there. If you find this confusing, check the Links and References section at the end of this article. There you’ll find some helpful resources.

Lines 21 through 25: Now we’re inside the subroutine. First, we set the accumulator to 16-bit, since we want to execute a 16-bit addition. We use phx to save the content of X on the stack. Next, we use tya to transfer Y into A. Then we clear the carry flag in preparation for an addition. Here’s a list of all transfer opcodes:

tax : Transfer Accumulator to X register

tay : Transfer Accumulator to Y register

tsx : Transfer Stack pointer to X register

txa : Transfer X register to Accumulator

txs : Transfer X register to Stack pointer

txy : Transfer X register to Y register

tya : Transfer Y register to Accumulator

tyx : Transfer Y register to X registerWhen using the transfer opcodes there are two important things to remember: First, observe from the list above that you transfer data between the index registers, or between the index registers and the accumulator. But the stack pointer can only be transferred from or to the X register.

Second, when transferring data between registers, the size of the data transferred is the size of the destination register. What does that mean? Remember that we can set the size of the accumulator and index registers independently. What happens if the index registers are set to 16-bit and the accumulator to 8-bit? If Y = $aaaa and A = $1111, then after a tya instruction, A will be A = $11aa. Since the accumulator was set to 8-bit, only one byte is transferred, even though both registers can hold 16-bit. This is an important thing to remember since: Transferring into a register set to 8-bit will leave the high byte of that register untouched.

In our example, we set the accumulator to 16-bit in line 21, so we don’t have to worry about that. Y is in A and X on the stack. So in line 25, we add X saved on the stack to A. This demonstrates a new addressing mode: stack relative addressing.

This is an extremely powerful addressing mode. In a later article, I will show you how to pass arguments to your subroutine by stack, rather than by register like we did here. This offers way more flexibility. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Stack relative addressing works like this: The effective address is calculated by adding the offset (the first operand of the opcode) to the current value of the stack pointer. The data at the effective address is then used for the operation. Earlier I told you that the stack pointer will always point to the last data pushed onto the stack plus one (another way to look at it is that the stack pointer is set to the first free address on the stack). In our case, we know that we pushed X onto the stack last, so we only have to add one to the stack pointer to obtain the address to the value from X we stored there.

Lines 26 through 28: Now we have the sum of X and Y stored in the accumulator. But we want it to be in Y, so we transfer the accumulator to Y. Since the index registers are set to 16-bit, both high and low byte are transferred to Y. Next, we pull X back into X from the stack. Why do we need to do this? We don’t need X anymore.

rts : ReTurn from SubroutineRemember that when we jumped to the subroutine, jsr stored the return address for the subroutine on the stack. The last instruction in the subroutine, rts, expects that the correct return address is on the stack. rts will simply pull whatever return address the stack pointer is pointing to and continue execution there. If we hadn’t first pulled X from the stack, then rts would jump to $1212 (the value from X we pushed onto the stack earlier); this would be an error, we don’t know what is at the address $1212. So executing any code from there would lead to chaos.

Line 17: After rts, we continue execution here and immediately tell the CPU to stop. That’s it. You wrote your first subroutine!

Conclusion

You learned a new important tool, the subroutine. Utilizing subroutines will make our code more modular and reusable. Next time, we will use subroutines to improve the sprite example from part four of this series. We will learn about Direct Memory Access and let the sprites bounce off the screen boundaries. Almost like a real game! As always, if you have any questions, please use the comment function below and I’ll try my best to help.

Links and References

- On the NESDev Wiki, is a good explanation of the stack.

- The C64 Wiki also holds a good entry on the stack.

- In this short article, the author explains everything covered in this article. Read this if you want to understand better how the stack and subroutines interact.

- All SNES Assembly Adventure code examples of this series on Github